In the winter of 2014, David New was seeking ways to build a bridge on his property north of Arlington. He invited Wayne Watne from the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife out to learn about permitting for a bridge. When Wayne spotted coho salmon in the stream, he suggested David reach out to Snohomish Conservation District to learn what programs were available for Stillaguamish landowners. It turns out that this unnamed tributary of Pilchuck Creek is an important spawning area for coho salmon. Around our office, it is commonly known as Trib 64.

The Problem

David noticed that salmon were getting caught in the weeds of his field. Yes, the field. The reed canary grass, a nasty invasive weed, had grown across the stream, and when at least six inches of water was present, coho salmon would swim over the field. When the water retreated, and due to the increased sediment caused by the reed canary grass, the fish would get stranded and die. This section of stream with impeded fish passage was over 1000 feet long. After this section, though, the waterway was passable for fish once it reached a forested area.

Like much rural/agricultural land in Snohomish County, this property had been in David’s wife Dari’s family for a few generations. Her grandfather bought the land from a timber company that used railroad lines to haul the logged trees off-site. When an uncle of Dari’s passed away, she and David hoped to buy the property, but a developer bought it first. As luck would have it, or simply the nature of the world, the recession hit and the developer went out of business. He had proposed 60 homes for the property, the New family bought it instead.

The New family’s affinity for fish goes back several years. David recalls the humpy’s (or pinks) from the 2005 run - thousands of them in fact. He said it was an amazing sight to see. In recent years, the numbers have not been near that high so the family hopes with the addition of their habitat project, they will see more fish in the future.

The Project

For the project, Kristin Marshall, District Senior Habitat Specialist, sought two funding sources - a Washington Department of Ecology (DOE) grant for 6.5 acres and the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP) for 26 acres. District Engineer Derek Hann was the main engineer for the project and luckily, David New is an engineer as well, so he provided additional designs as an in-kind contribution.

The Adopt A Stream Foundation was our contractor, and over the years, we’ve had all of our crews - Washington Conservation Corps and the Veterans Conservation Corps - on site. An assortment of volunteers has happily come out to plant native trees and shrubs and enjoy the bucolic scenery as well. David mentioned being “so grateful” for all of our help, and he specifically named District habitat specialists Ryan Williams and Carson Moscoso as being really “great to work with.”

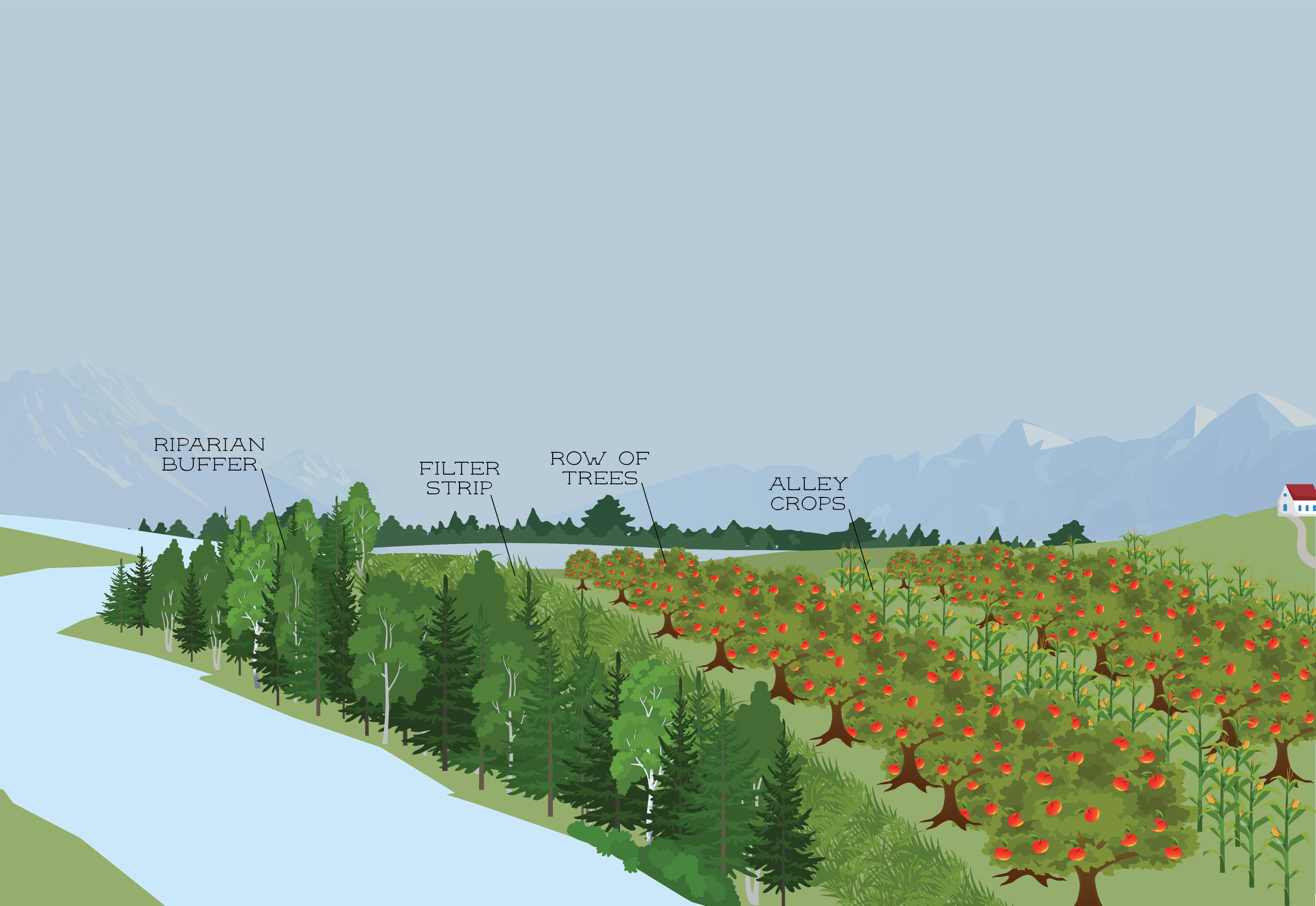

Through CREP, there will be four years of crew maintenance provided to the New family for keeping the reed canary grass down, and there will be check-ins for at least the next decade. Our goals with this project are the long-term health of Pilchuck Creek with the re-establishment of a forest canopy, a vegetated streamside, and by facilitating fish access to spawning areas. The challenges remain the ongoing battle with reed canary grass and the migrating channel. Rivers and streams tend to go where they want - hence this project was based on what was naturally occurring, instead of trying to re-route the waterway.

We are grateful to the New family for their willingness to work with the District and our project partners for critical salmon habitat. The side channel created on his property will benefit salmon for years to come -enabling them to reach spawning grounds that were inaccessible before the project. Many layers of work have already been done on the property - this is a well-loved and utilized

family legacy.

If you’re looking to restore your property like David, contact our Habitat Team for a site visit or just call or email with your question. We’re happy to help out. Contact us at 425-335-5634, email

habitat@snohomishcd.org, or visit snocd.org/habitat.